More Intelligent Birds (Like More Intelligent Humans) Have Evolutionarily Novel Preferences

The Savanna-IQ Interaction Hypothesis about the effect of intelligence on individual preferences and values may be applicable to other, nonhuman species.

I propose and present extensive evidence for the Savanna-IQ Interaction Hypothesis (or the Hypothesis) in my book The Intelligence Paradox: Why the Intelligent Choice Isn’t Always the Smart One. Briefly, the Hypothesis suggests that, because general intelligence evolved to solve evolutionarily novel (but not evolutionarily familiar) adaptive problems, more intelligent individuals are more likely than less intelligent individuals to acquire and espouse evolutionarily novel preferences and values that our ancestors did not have. In the book, I show, for example, that more intelligent children are more likely to grow up to: be left-wing liberals (even though liberals are stupider than conservatives); be atheists; prefer sexual exclusivity (but only if they are male, even though more intelligent men and women are actually more likely to have extramarital affairs); be nocturnal; be vegetarian; drink more alcohol; engage in binge drinking and get drunk; smoke more cigarettes (but only in the US, not in the UK); use illegal psychoactive drugs; and commit fewer crimes (although what matters is evolutionary novelty, not criminality per se). By now there appears very little doubt that, among humans, general intelligence facilitates the acquisition and espousal of evolutionarily novel preferences and values. More intelligent people are more likely to want to do things that our ancestors did not do. Now a recent article in Biology Letters suggests that the “intelligence – preference for evolutionary novelty” connection may not be limited to humans and may extend to other, even very distant species as well.

In their article “Brains and the City: Big-Brained Passerine Birds Succeed in Urban Environments,” Alexei A. Maklakov and colleagues at Uppsala University in Sweden examine the relative brain size (net of body size) and behavior of 82 species of passerine birds from 22 families. Both across and within species, relative brain size is a very precise measure of intelligence. Among humans, for example, head circumference is one of the two strongest physiological correlates of general intelligence, along with myopia (near-sightedness). Yes, once again, the stereotype is true (as all stereotypes are): Eggheads with four eyes are more intelligent than their classmates. And pinheads indeed are less intelligent. Head circumference and myopia are both much more strongly correlated with general intelligence than height or physical attractiveness, for example.

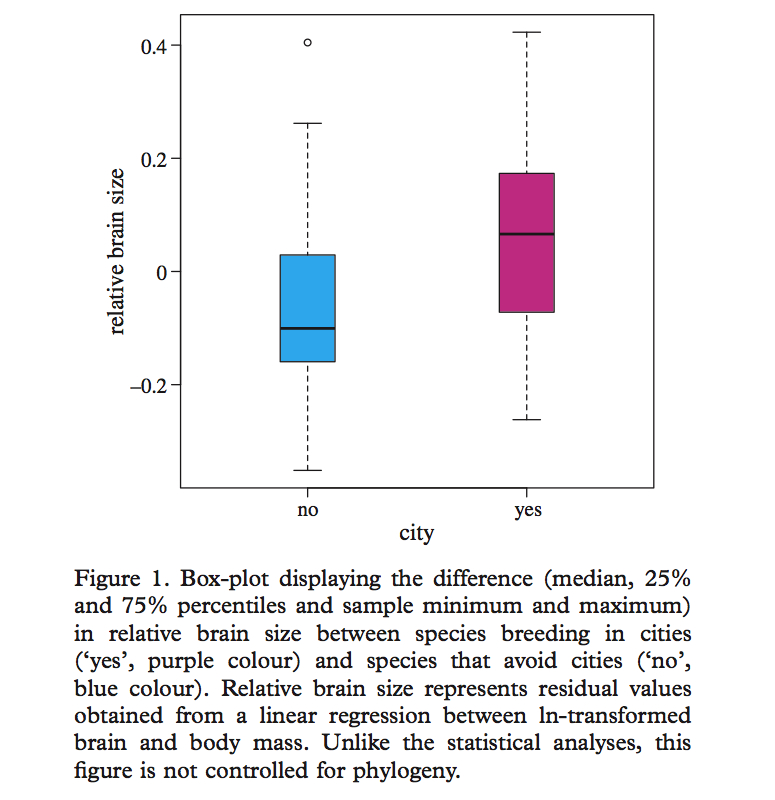

Maklakov and colleagues classify each species as either successful urban inhabitants (those who are able to breed inside cities successfully) or urban avoiders (those who cannot). As the figure below shows, the city breeders on average have significantly larger brains than urban avoiders.

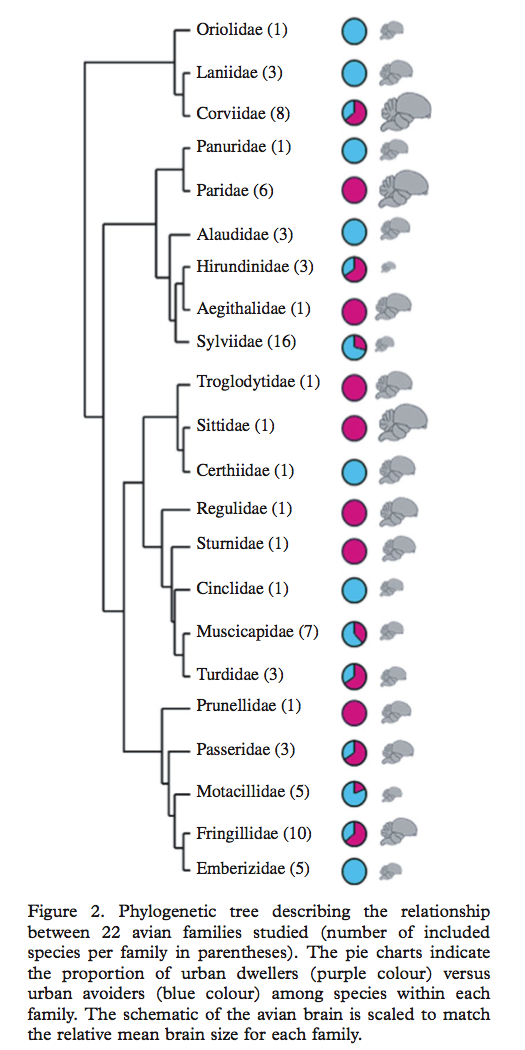

The following figure (which is one of the most beautiful graphics that I have ever seen in a scientific article) shows that, across the 22 families of passerine birds, there is a positive correlation between their mean relative brain size and the proportion of the species in the family that are successful city breeders. The larger the average relative brain size of the family (and hence the higher the average intelligence), the more likely they are to have an evolutionarily novel preference to live in a city, exactly as you would expect if you applied the Hypothesis to avian species.

Here

is a picture of a Blue Tit managing to open a foil cap of a milk bottle

left on the front porch of a house in a city. Blue Tits have long

been known to possess the evolutionarily novel ability to drink milk

from a factory-sealed glass bottle. The Blue Tit belongs to the

family Paridae, which, according to the figure above, has one

of the largest brains of all passerine birds and 100% of whose species

are successful urban breeders.

Here

is a picture of a Blue Tit managing to open a foil cap of a milk bottle

left on the front porch of a house in a city. Blue Tits have long

been known to possess the evolutionarily novel ability to drink milk

from a factory-sealed glass bottle. The Blue Tit belongs to the

family Paridae, which, according to the figure above, has one

of the largest brains of all passerine birds and 100% of whose species

are successful urban breeders.

Note that Maklakov et al.’s analysis does not mean that more intelligent birds are better able to solve adaptive problems in general. All species that have not gone extinct, even the smallest-brained, least-intelligent avian species, can solve the evolutionarily familiar adaptive problems of procuring food, finding mates, and raising the young. Otherwise, they would have gone extinct long before there were cities (and ornithologists to study them). The only problems that less intelligent birds cannot solve are those presented by environments that did not exist throughout most of their evolutionary history – evolutionarily novel adaptive problems.

Thanks to my friend Richard Lynn for alerting me to the Maklakov et al. article in Biology Letters.

Follow me on Twitter: @SatoshiKanazawa